Taking your understanding of lean manufacturing from a list of tools to a clear philosophy

Have you ever felt a bit confused about what exactly lean manufacturing really means? You probably find craft and mass production much easier to understand. They can be clearly defined. But at times lean can seem like a collection of different tools without a central philosophy.

If that’s the way you feel about lean manufacturing then trust me, you’re not alone. But lean really isn’t hard to understand, it’s just been explained badly. And I think there is a good reason for that.

As you will soon see, applying some lean tools is easy. But actually applying the philosophy of lean can be a bitter pill to swallow.

So the typical consultant or trainer will show you how to apply a few of the tools of lean manufacturing. Because he knows you will find this easy! But he won’t tell you what you don’t want to hear. Implementing the lean philosophy throughout an organisation is a huge and difficult transition.

But it is only by taking these big steps that you will transform quality and productivity.

A brief history of manufacturing

I’m sure you already have a good idea about the different types of production that have been used in history. But it will help you understand the philosophy of lean manufacturing if you consider how it has developed.

In the beginning jobs were divided into ‘men’s work’ and ‘women’s work’. Next there was division into farmers, craftsmen, soldiers etc. In craft production one person may make a complete product from start to finish using highly adaptable tools. But often craftsmen are divided into more specialized roles. When craftsmen make machines the parts are filed to fit to together. If you need a new part it has to be filed to fit by another craftsman.

In the beginning jobs were divided into ‘men’s work’ and ‘women’s work’. Next there was division into farmers, craftsmen, soldiers etc. In craft production one person may make a complete product from start to finish using highly adaptable tools. But often craftsmen are divided into more specialized roles. When craftsmen make machines the parts are filed to fit to together. If you need a new part it has to be filed to fit by another craftsman.

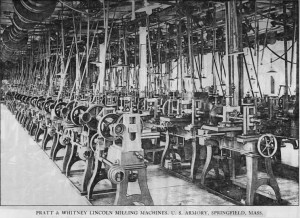

19th century American gun makers showed it was easier to make machines from interchangeable parts that fit together like Lego. In this ‘American system’ or ‘armoury practice’ a row of machines, each making a simple cut, would produce a standard part step-by-step. These machines didn’t need skilled craftsmen to operate them. Each machine was set against a gauge, and the gauges were set against a master part. This meant that all the parts would fit together without needing to be filed at the end. So assembly didn’t need skilled craftsmen either. Since the workers actually making things weren’t skilled they weren’t trusted to check the quality of their work. So inspectors and foremen were hired to maintain quality.

19th century American gun makers showed it was easier to make machines from interchangeable parts that fit together like Lego. In this ‘American system’ or ‘armoury practice’ a row of machines, each making a simple cut, would produce a standard part step-by-step. These machines didn’t need skilled craftsmen to operate them. Each machine was set against a gauge, and the gauges were set against a master part. This meant that all the parts would fit together without needing to be filed at the end. So assembly didn’t need skilled craftsmen either. Since the workers actually making things weren’t skilled they weren’t trusted to check the quality of their work. So inspectors and foremen were hired to maintain quality.

Henry Ford applied armoury practice to the point where each worker only carried out the simplest of operations. He was able to do this because he designed his car to be easy to make in this type of factory. Then he introduced the moving assembly line and mass production was born.

There is a steady progression away from skilled craftsmen using versatile hand tools and responsible for the quality of their own work. This is replaced by unskilled workers repeating simple operations on specialized machines with responsibility for quality given to inspectors.

The Toyota Production System – Lean Manufacturing by another Name

In 1950 Eiji Toyoda wanted to save his family’s small car business – Toyota. He visited the vast Ford factory in Detroit for ideas. But he quickly realised that they could never compete by adopting mass production. The Japanese market needed small batches of several different vehicles. Their unions were strong and they didn’t have the immigrant work force that western manufacturers relied on for cheap labour. And there was another problem…

In mass production each of the 300 different steel panels for a car body is stamped on a different machine. They didn’t have money for hundreds of stamping machines. But Toyota’s chief engineer Taiichi Ohno found a solution. They must reduce the tool change time on the stamping machines. Then they could produce all the panels in small batches on just a few machines. Using rollers and simple adjusters they reduced the time from a day to just 3 minutes. After 10 years of development they could now efficiently produce a whole car body using just a few machines.

To their surprise parts produced in small batches actually cost less than mass produced parts! They didn’t have the cost of carrying inventory. But most importantly they could detect and correct stamping mistakes almost instantly.

At that point the essence of lean manufacturing was born. The trend away from versatile craftsmen was reversed. They kept the efficiency of machine made interchangeable parts. But they didn’t have unskilled workers doing repetitive jobs who didn’t notice quality. The production workers were making a wide range of different parts throughout the day. They were responsible for the tool changes, for checking quality and for getting to the root cause of an issues.

While the revolution in production methods was taking place there were also huge changes in labour relations. Redundancies and union action resulted in a new deal with the workers. They were guaranteed jobs for life with unheard of benefits but they were expected to do any job asked of them.

Ohno saw the inspectors, foremen, cleaners and repair men in mass production factories as ‘muda’ – waste. They weren’t adding value to the car. Instead workers were organized into teams with complete responsibility of their section of the assembly line. Instead of an idle foreman their team leader worked with the team. They did their own cleaning, repairs and quality-checking. The team even had time to discuss improving their process.

Allowing problems to move down the line before being inspected at the end was just more waste. If the problem wasn’t dealt with immediately then it would be repeated. So every worker had a cord above their work station. If they found a problem they couldn’t fix they could stop the line and the team would help them fix it. Then they would ask the ‘5 whys’ to get to the root cause. And they would find a way to stop it happening again ‘poka yoke’ (failure proofing).

The lean plant has two key organizational features, “It transfers the maximum number of tasks and responsibilities to those workers actually adding value to the car on the line, and it has in place a system for detecting defects that quickly traces every problem, once discovered, to its ultimate cause” (The Machine That Changed the World, Womack et al)

The transfer of responsibility down to those adding value was extended throughout the business. Subcontractors were organized into tiers so Toyota only dealt directly with ‘tier 1’ suppliers. The tier 1 suppliers were responsible for managing tier 2 suppliers and often also for the design of complete sub-systems. Similarly the sales force, who is after all dealing with the customers on a day to day basis, takes responsibility for gathering marketing data about the customers’ preferences.

Lean Manufacturing as a Gold Standard

The methods developed at Toyota were adopted by other Japanese companies but for a long time went unnoticed in the West. By the 1980’s there was a growing awareness that the west was falling behind the productivity of Japan. In 1984 the International Motor Vehicle Program at MIT began a 5 year study. They would first study all of the tasks needed to make a car. Then they would visit producers around the world to see how they carry these out.

They found that the principles used by Toyota could work in every industry around the world with a huge benefit. They called these principles Lean.

So nobody invented ‘lean’! Toyoda, Ohno and others at Toyota created the ‘Toyota Production System’ and then years later a group of American professors studied it, called it ‘lean’ and told the world about it. The book they wrote is the clearest and most detailed explanation of the lean manufacturing system I’ve read. If you want to learn more then get this book.